Author: Omri Brinner and Chantal Elisabeth Hohe.

2022 brought about several game-changing developments in the Middle East and beyond. These events - from domestic political instability, through the weakening of American influence in the region, to the protests in Iran - will all leave a mark in 2023, a year that is shaping to be decisive for the Middle East’s future.

Of the many things to monitor in the region during 2023, four issues stand out the most, largely due to their international significance. These are the American involvement in the Middle East; climate change and the region’s efforts - or lack of - to counter it; the domestic upheaval in Iran and its global impact; and the economic situation across the region, with a growing number of countries in economic disarray (Turkey, Lebanon, Egypt and Yemen).

The US in the Middle East

Going into 2023, the United State’s role in the Middle East is undefined. Had it been clear and obvious, American officials wouldn’t have to reiterate that their country will remain pivotal as it once was. The facts on the ground suggest less American physical involvement. There are less American troops in the region; American diplomacy has been weakened; and one is much more exposed to alternative soft power than before. In that sense we are expected to see declining American presence across the region. Diplomatically, the US is losing grip as well. While it largely has Israel on its side in its competition with China and Russia, other allies - most notably Saudi Arabia - are becoming less and less dependent on the US, fueling a multipolar world where the US is now one of many, rather than the one. The US can stay assured that it will continue to have leverage over several individuals and countries in the coming year, but all in all - and much due to the multipolar inertia across the region - this leverage is not infinite, and further distancing from American policies are likely to follow. This dynamic played out in the relations between President Biden and the Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin-Salman, where the latter refused to give-in to American pressure on oil prices, proving that the American leverage on him and his country is limited. In other words, American superiority will not only continue to be challenged from afar, but also from within the region itself.

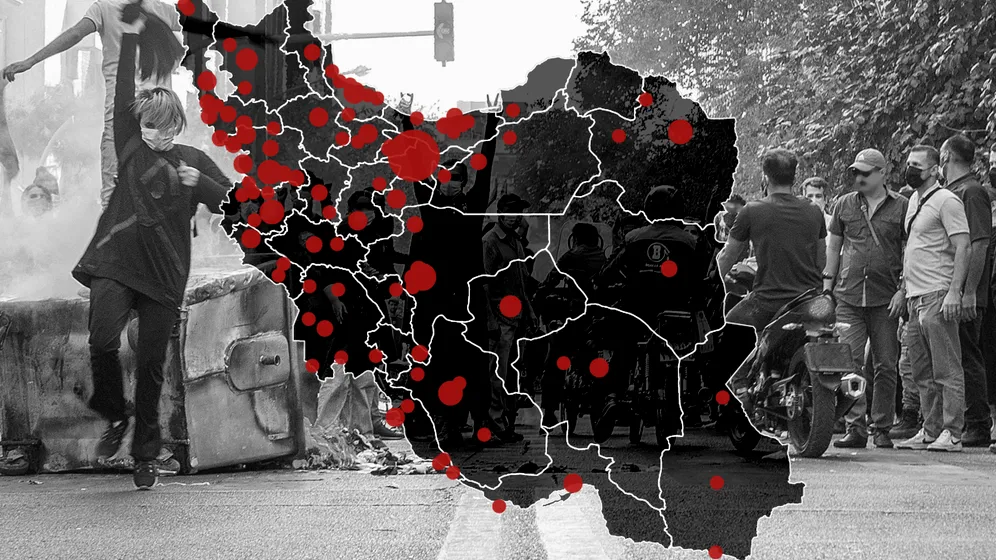

Iran

2023 might very well be the year of the Persian Spring. The revolutionary protests that began in September have the potential to spin the regime out of control and to create a new reality in the country, and the region. What started as a social protest against the state’s brutality and the killing of Masha Amini has developed into a full regime-change movement, with the slogan “death to Khamenei” gaining momentum and legitimacy on social media. It is of course possible that the harsh and lethal crackdown by the state will break the back of the revolution, but these past few months and the ones to follow will certainly change Iran and affect the region as a whole, whichever way the wind blows.

Furthermore, in light of the internal turmoil and the fact that the Iranian nuclear deal is all but alive, it is likely that Iran will push to both enrich as much uranium as possible and to create destabilizing chaos across the region in the coming months. All in all, what happens in Iran during 2023 will determine the near future of the Middle East.

Climate

After a rather unsuccessful COP27 failed to produce actionable policy solutions or real commitments from the international community, a decisive year lies ahead for the Middle East, where people will continue suffering from the consequences of the climate crisis. Most prominently, water scarcity will lead to an increasingly dire situation, fueling food insecurity, economic downturn, civil unrest, and violent extremism. That said, several innovative start-ups and promising technologies are on the rise, with the GCC countries upping the funding to accelerate developments in the field. Hope now lies upon the Abu Dhabi COP28, set to take place in November and, ironically, hosted by UAE’s National Oil Company CEO, with civil society organizations and academia urging for serious action.

Economy

A cleavage in economic performance is increasingly visible among Middle Eastern countries, with the oil-based GCC monarchies witnessing continuous growth - whereas others are facing economic decline, leading to or exacerbating existing socio-political turbulences. The economic outlook for 2023 indicates that inflation is likely to surpass 30% in numerous countries, with Syria at 63% and Lebanon at a staggering 167% . Further regional actors, such as Iran, Turkey, Egypt, and Yemen, face economic hardship while also having to tackle political challenges, civil unrest, and violent conflicts. Overall, domestic and international factors - such as the war in Ukraine - are likely to deepen a looming recession and the energy crisis. While it is likely that wealthy GCC countries will continue to support struggling regional allies, countries such as Yemen, Libya and Lebanon will continue to be used as arenas for proxy wars, further deepening their economic troubles.