By: Ludovica Brambilla, Arslan Sheikh and Esther Brito Ruiz

The Urban World

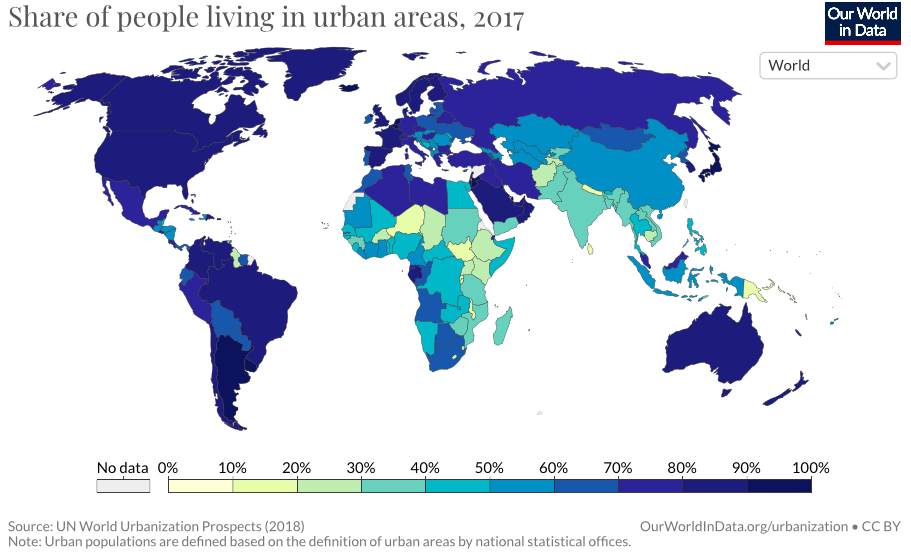

The world is becoming increasingly urban. For the first time in history, most of the world population resides in cities – and the challenges of human security have evolved accordingly. Human security is generally considered to encompass economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community, and political security. In line with urbanization, issues of lack of access to health or education centers have tended to decrease, but problems associated with social stratification, urban segregation, and unaffordability have become more prominent. Nowhere is this more evident – or pressing – in modern cities than in the primordial problem of access to housing.

As city centers become denser, competition for space has becomes fiercer and through it the struggle for housing supply and conditions of tenant protection worsens. This drives up prices, making housing unaffordable for many. In turn, this acts as a facilitator of socio-economic segregation and a core driver of urban inequality. In the world’s megacities – those with more than 10 million inhabitants – this has often become especially dire. Currently, 20% of the world population – about 1.6 billion people – lack access to adequate housing. While not often discussed in political science, access to housing stands as a foundational element – and a precondition for – human security.

Human Security Implications of Housing

The local governments of different countries are trying to implement innovative solutions to tackle the housing problem ranging from mandatory social housing quotas in Helsinki to creating backyard homes in Los Angeles. However, when these initiatives are unsuccessful in managing the problem, housing creates multilevel human security crises. These often include the proliferation of slums, the advance of gentrification, and both increased evictions and homelessness. With the COVID-19 pandemic driving forth a new global housing crisis and compromising the economic security of millions, we see the fault lines within our cities and societies widen further.

Slums

Slums are mainly the product of unplanned urbanization and can represent the most common form of housing in many expanding cities of the developing world – such as Kibera, New Delhi, Mumbai, or Manila. They are a form of informal housing – often illegal – which can be defined as having the following characteristics: unsafe or inadequate infrastructure; overcrowding; limited or no access to basic services – such as running water or electricity; and no secure tenure, due to having no land-rights on the property.

Slums emerge and continue to proliferate in less developed countries due to the the inability to meet the demands of a growing population; nearly about one billion people occupy slums. The key challenge of slums is their large size and magnitude. The total number of slum inhabitants has grown, even as the proportion of slum population has declined. The people living in worst slum conditions are found in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia – regions with a low Human Development Index and persistent poverty challenges. Asian cities host sixty-one percent of the global slum population, with India and China alone having 153 and 171 million slum dwellers respectively. The causes of concern for slum dwellers are manifold. They not only are at risk of being the victims of forceful evictions, but are also prone to various environmental risks such as steep slopes, river and canal beds, marshes and near polluted areas like garbage dumps. Besides that, they often lack the conditions required to live a dignified life. The low-income residents living in slums are also displaced from their neighborhood because of gentrification.

Gentrification

Gentrification underlines the ocial and economic divisions that exists within the world'cities. It is a powerful force capable of mutating cities and bringing new private and public capital and services into neighborhoods that have suffered from prolonged disinvestments. But gentrification strongly differs from urban renewal, in fact, the rising of property value and the lack of affordable housing cause exclusionary displacement. The pandemic has further exposed and worsened these dynamics which has ultimately led to the displacement of low-income and minority residents.

As a result, the long-term residents that have created the unique social fabric of the neighborhood are forced to move. Minority groups are most often damaged by this process. For instance, in large American cites, displacement of minorities has followed gentrification and impacted significant percentages of black and hispanic residents that can no longer benefit from the new services that come with new local investments. This results in the erosion of the social networks on which families rely on, fostering isolation. As areas have gentrified, low-income families face severe housing crises which sometimes even push them into homelessness. More often, poorer residents move on the fringes of cities further increasing pockets of poverty, urban decay and ultimately, segregation.

Once we recognize the impacts of gentrification on social justice and human security, we cannot separate this problem from the urge of adequate policies. The possible solutions lay on rent control policies and progressive land tax combined with the restriction of predatorial investment schemes that can prevent evictions and homelessness.

Evictions & Homelessness

As mentioned, dynamics like gentrification can drive forced evictions, which only increases in times of crisis. In 2020, the UN's special rapporteur on the right to housing issued an official call to governments requesting they halt all evictions until the end of the pandemic. That year, in the United States alone around 30 to 40 million people were identified to be facing or at risk of eviction. Similar trends and forced evictions manifested globally – with cases in South African, Brazil and Kenya being notable. The fear of eviction threatens core rights of urban residents and reflects trends of social disparities – affecting LGBT+ youth, mono-parental families, and people of color disproportionately. When eviction occurs, it often implies the loss of access to other basic services.

Derived from evictions and urban inequality is homelessness. This phenomenon is conditioned by issues as varied as racism and discrimination, gendered violence, and mental health, among others. Currently, around 2% of the global population is homeless – which is set to continue to increase in line with urbanization. Homelessness is an expression of failures in governance and has turned into a global human rights crisis. It is important to note that local governments can worsen the crisis by taking stances of criminalization or imposing harsh conditions that seek to drive the homeless away to other areas. A visible example of these policies is the installation of hostile architecture. By virtue of an absence of housing, homelessness compromises every aspect of human security.

Conclusion

To address the issue of housing insecurity, political leaders should look beyond the affordability of basic shelters. Instead, possible solutions need to focus on improving services in critical neighborhoods, taking advantage of public land to build new social housing in parts of the city suffering under market pressure. In order to get to a new reality of accessible, inclusive and sustainable cities, a strong collaboration between the public-private and nonprofit sectors is needed. Effective solutions also require the inclusion of representative local social actors and community-based organizations in decision-making processes, which will be fundamental in preserving and enhancing the city’s cultural identity. There exist viable solutions, what remains wanting is the political will for implementation.