Authors: Idriss El Alaoui Talibi and Michele Mignona (Edited by Iris Raith) - Defense & Procurement Team

Introduction

Since October 2023, tensions in the Red Sea have reached unprecedented levels, largely due to a series of aggressive manoeuvres by Houthi forces stationed in Yemen. These actions have included multiple drone and missile assaults targeting both Israeli territories and various vessels—both commercial and military—operating in the region. The Houthi attacks are interpreted as direct responses to Israel's military campaign in Gaza.

To address the escalating threat, the U.S. began Operation Prosperity Guardian in December, a multinational military initiative aimed at safeguarding the Red Sea against further Houthi incursions. Subsequently, beginning on January 12, the U.S. and UK have jointly executed targeted strikes against Houthi installations within Yemen in the aftermath of the beginning of Operation Poseidon Archer. This consists of a coalition of states willing to conduct offensive operations in the region to deteriorate Houti’s military infrastructure.

Both President Biden and Prime Minister Sunak emphasized that the military strikes were a direct response to the attacks on ships in the Red Sea, which endangered trade and threatened freedom of navigation. This is especially pertinent given that approximately 15% of global seaborne trade typically passes through the Suez Canal. Consequently, this shift is causing substantial global economic losses.

Who are the Houthis?

The Houthis are an armed political and religious group supporting Yemen's Shia Muslim minority. Aligned with Iran's "axis of resistance", they emerged in the 1990s under Hussein al-Houthi's leadership, now led by his brother Abdul Malik. Since 2000, they have battled the Yemeni government for autonomy in northern Yemen, expanding influence during the 2011 Arab Revolt. By 2016, they had seized significant territories in Yemen’s West.

Concerned about potential Houthi-Iran alignment, Saudi Arabia formed a coalition to intervene but has been unable to dislodge Houthi control despite years of airstrikes and battles. Although Iran denies supplying the Houthis weapons, instead claiming political support, there is widespread recognition of a tangible Iran-Houthi relationship. In this context, Houthi attacks may pose a greater threat to global security than Gaza's conflict. Indeed, based on pragmatic security and economic calculations, the Houthis' actions could disrupt the delicate regional equilibrium, carrying significant escalation risks despite their relatively small size.

Regional and International Responses

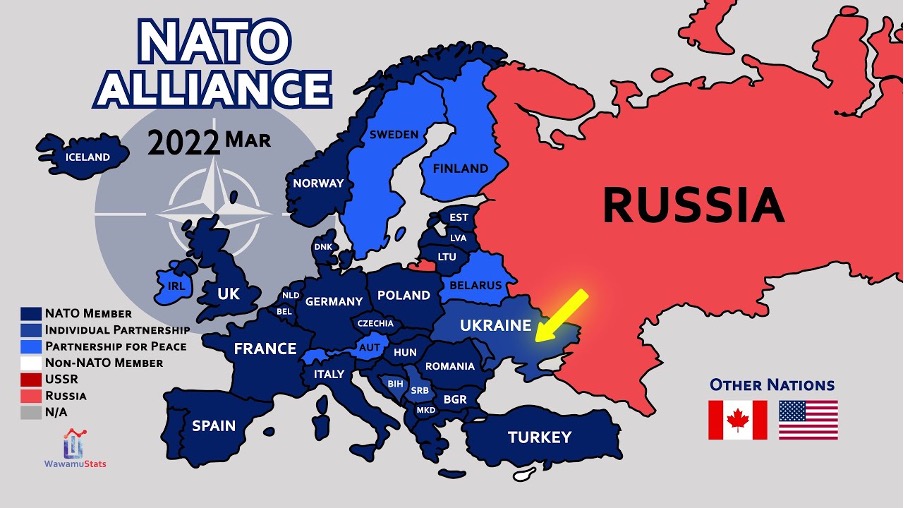

In response to the Houthis’ attacks and their impacts on international trade and freedom of navigation, Operation Prosperity Guardian was launched to safeguard the security of the southern part of the Red Sea. This operation includes over 20 countries, including the UK, Canada, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain, with Bahrain being the only Arab country in the coalition.

This initiative announced the beginning of a series of attempts, outside of the umbrella of Operation Prosperity Guardian, to repel the Houthis’ attacks, as more than a dozen separate attacks have been conducted, 11 of which have been conducted by the U.S. only. Indeed, since the beginning of the Houthis’ attacks on various vessels, the U.S. has seen its involvement in the region increase with intensified efforts to put a stop to the Houthis’ attacks. A month ago, the U.S. Department of State officially announced the designation of Ansarallah (Houthis) as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist group. Moreover, both the UK and the EU are expected to launch separate initiatives to counter the Houthis’ attacks in the Red Sea.

Economic Implications

As mentioned, these assaults against commercial vessels have caused deep economic losses, as it pushed shipping companies to steer clear of this vital trade route. Thus, shipping vessels are now constrained to change itineraries and take the longer route around the Cape of Good Hope, situated at the southern tip of Africa. This alternative corridor extends the journey by over 3,500 nautical miles (6,500 km) and nearly two weeks of sailing time for each voyage, thereby substantially inflating shipping expenses.

According to statistics, more than 20,000 vessels navigate the Red Sea yearly. As such, this crisis creates a serious challenge to both international maritime security and international trade. Although the Houthis are said only to be targeting vessels linked to Israeli interests, the risk of security incidents in this vital shipping lane is seriously affecting the carriage of commodities between major world economies, including the oil-exporting countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), the European Union, the U.S. and China.

Alongside these countries, India also ranks high among the most affected countries by the ongoing Red Sea crisis. Indeed, India is heavily dependent on the Red Sea route through the Suez Canal for its trade with Europe, North America, North Africa and the Middle East, as these regions represent more than 50% of India’s exports ($217bn), according to CRISIL Ratings. This showcases the extent of this crisis’ implications.

Looking forward

The current Red Sea crisis has highlighted the unequivocal importance of this location for geopolitics. With both commercial and strategic implications, the Houthi’s actions have pushed the international community to cooperate to counter these attacks and safeguard freedom of navigation. While the U.S. was eager to engage a military coalition with the initiation of Operation Prosperity Guardian, the EU also began to step out of its shadow by introducing Operation Aspides, if so, with a delay due to its still reactive strategy. It remains to be seen if and how this crisis will de-escalate in the future, as this will be influenced by the war in Gaza and the destabilization of the region. Nevertheless, next to military cooperation, it will certainly be vital to engage in diplomatic efforts aiming to de-escalate the enduring Yemeni conflict by including all parties involved and affected.