Authors: Sonia Martínez Girón (ITSS Executive Director) and Anna Lorenzini (Middle East Team)

(Photo by Christelle Hayek on Unsplash)

Introduction

Once known for its cultural richness and economic resilience, Lebanon is located in the Eastern Mediterranean Levant region with over five million inhabitants and no Head of State. The complex interplay of economic and political mismanagement, multiple corruption cases, lack of accountability, instability, unrest and poor freedom of expression do not bolster any sociopolitical or economic positive change to thwart the spiralling crises affecting the Lebanese people. Currently, around 80% of Lebanon’s population lives under the poverty threshold.

Politics

Lebanon has been in a profound economic and political crisis since the banking system collapsed in 2019, damaging the currency, increasing poverty, and paralysing most of the country. Prime Minister Saad Hariri’s resignation in October 2019 triggered a series of unsuccessful attempts to form a new government. The ensuing political vacuum left Lebanon without a coherent leadership to address pressing economic challenges. External factors, including regional conflicts, have further complicated the political situation, hindering the formation of a government capable of steering the country out of crisis.

Lebanon's political landscape, characterised by a delicate sectarian balance, has been a source of strength and weakness. The confessional system, designed to distribute power among various religious communities, has often resulted in political gridlock, impeding effective governance. The parliament extended army commander Joseph Aoun's tenure last December to prevent a leadership vacuum. The army, which was rebuilt during the civil war, is viewed as essential to keep the country stable in the face of emergencies (e.g. an imminent border clash with Israel). Besides, the parliament prolonged the term of Lebanon's Internal Security Chief, a Sunni Muslim. Hence, the absence of a stable government capable of implementing crucial reforms has exacerbated the economic crisis.

Uncertainty in its governance structure persists, with rising vacancies in key governance positions. While Lebanon's economic and institutional crisis weakens its international standing, numerous players remain involved in the Lebanese geopolitical scenario. The prolonged delay in electing a new president and increasing polarisation are not easing this knot. Despite reaching an agreement on maritime borders, tensions persist. In addition to the traditional tensions with Israel, the presence of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) in the south of the country has become contentious.

Tensions arose from a UN Security Council resolution in August 2022, allowing UNIFIL to act independently of local authorities, consequently altering the relations between UNIFIL and the Lebanese army. The Group of Five (formed by Saudi Arabia, Egypt, France, Qatar, and the United States) was created to facilitate the resolution of Lebanon's political crisis. Unluckily, in July 2023, the shortfall of results from their second meeting worsened the state of affairs.

Economy

Lebanon’s fifteen-year-long civil war (1975–90) severely damaged this country’s economy. Due to its heavy dependence on banking and financial services since the conclusion of the civil war in 1990, along with the neglect of the agricultural and industrial sectors, Lebanon heavily relied on imports to fulfil the needs of its citizens. The Lebanese Central Bank subsidised wheat and fuel to make these commodities affordable, leading to significant challenges in the face of mounting public debt, a lack of economic reforms, and an increasing current account deficit.

In the early 2010s, Lebanon's economic issues worsened, and in 2019, widespread protests erupted against economic inequality, corruption, and poor public services, reaching a breaking point. A series of intertwined crises, starting with an economic downturn, followed by the impact of COVID-19, and culminating in the Beirut Port explosion, have severely impacted Lebanon. Besides, after the 2020 Port explosions, the lack of accountability has bolstered poverty in the country. Among these, the economic crisis has had the most substantial negative effect, with the Lebanese currency, the lira, experiencing a drastic depreciation of over 90% against the US dollar on the parallel market.

This configuration has resulted in hyperinflation, soaring prices of essential goods, and a sharp decline in the purchasing power of citizens, contributing to widespread business struggles, surging unemployment, and increased poverty rates. Indeed, the Lebanese currency's value has plummeted by over 95%. With the Central Bank depleting foreign reserves, discontinuing subsidies on crucial imports, and simultaneously witnessing a surge in electricity, water, and gas prices, essential utilities have become a luxury for many. A Human Rights Watch survey from November 2021 to January 2022 revealed that the median household income was only US$122, with 70% of households struggling to meet basic expenses. While the crisis affects the entire population, vulnerable groups such as women, children, migrant workers, refugees, and individuals with disabilities bear a disproportionate burden.

The population sector that appears to be most vulnerable to unemployment includes the migrants from Syria and Palestine, the inhabitants of North Lebanon, the youth and the women. Unemployment numbers have more than doubled since 2019. The unemployment level reached 29.6% in 2022. The Italian government estimated that 27.5% of people would be unemployed in 2023.

The younger generation in Lebanon faces a dilemma, resulting in many choosing to either leave the nation or feel closed in. High rates of youth unemployment and the burden of debts incurred for university education in a system controlled by the corporate sector further discourage young people from envisioning a future within Lebanon. The youth is also experiencing significant challenges in pursuing their education degrees, as the country's universities have raised tuition costs to an unprecedented rate, prompting many students to abandon their studies. Youth unemployment rocketed to 47.8% in 2022. Current data on out-migration could look better for the economy. In a recent survey, 77% of Lebanese youth between 18 and 24 years indicated their wish to leave the country to find better opportunities elsewhere. Even those youngsters with jobs who are paid in dollars report feeling insecure.

Food Insecurity

Around 2 million people face food insecurity in Lebanon. Alas, the situation is expected to get worse in the upcoming months. According to the IPC predictions, it is expected to reach 2.26 million people by April. Specifically, the refugees are the most affected. Vis-à-vis the nearly thirteen-year conflict in Syria, Lebanon has hosted over 1.5 million refugees, maintaining one of the largest refugee populations. This was the first time that the IPC Acute Food Insecurity analysis included Palestine refugees in Lebanon and Palestine refugees from Syria. Currently, many people are dependent on food assistance in Lebanon. While aid keeps flowing into Lebanon, people's needs still escalate due to local and global turbulences.

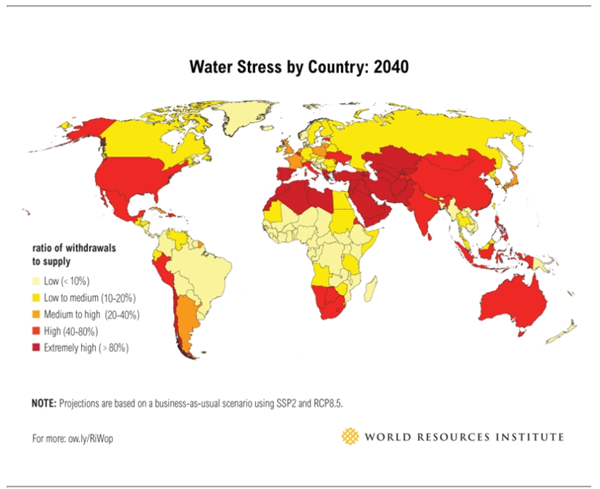

As we have seen, the food crisis in this country is linked to several other critical topics. It is necessary to talk about the water crisis. Regarding water use in the Middle East, agriculture uses 85 per cent of the total fresh water. The poor water governance and the inefficient irrigation systems augment this country's water shortages. As if this was not enough, water pollution affects the quality of drinking water, agricultural production, and food safety.

Needless to say, water shortages have affected agriculture. Water scarcity resulted in poorer agricultural yields, making it more difficult for farmers to sustain their livelihoods. A recent study discovered that significant rural areas are experiencing decreased production, particularly in coastal locations where citrus fruits and olives are cultivated and at higher elevations where deciduous fruit trees are. Areas depending on irrigation systems in the Beqaa Valley, the country's primary agricultural region, are being harmed by increased groundwater stress and loss of water resources. Farming communities in these areas have already seen severe consequences, such as unreliable household food supply.

The ongoing agricultural crisis is a source of concern. Lebanon's prolonged neglect of the agriculture sector resulted in direct import reliance, which Lebanon still suffers today. Mainly, almost 80% of the food consumed in Lebanon is imported. First, agricultural labour has traditionally been precarious in Lebanon. Second, the high dependence on the agricultural labour of refugees has exacerbated the devaluation of farm workers. Third, more than 20 per cent of heads of households engaged in farming are highly vulnerable. Women farmers, marked by increased poverty, account for 9 per cent of the total farmers.

Over and above that, Lebanon's food resources are squandered due to several drivers. On the one hand, the multiple crises that have affected Lebanon since 2019 have damaged the food security status of its inhabitants. The national and local crises have a direct impact on food security. Referring back to the port incident, grain silos that were stored in the port were turned into rubble during the port blast in 2020, consequently boosting food insecurity in the region.

On the other hand, other global turmoils are impacting food security in Lebanon. To name a paradigmatic example, the Russo-Ukrainian War has added further pressure to the already exhausted Lebanese economy with rising food costs. In fact, 96% of the wheat consumed in Lebanon is imported from Ukraine and Russia. This configuration leads to considerable direct and indirect food price increases. Besides, due to the devaluation of the lira, food prices are currently increasing further. Indeed, food prices have surged by 332% since June 2021. Additionally, the WFP food aid cuts will not help this crisis. Unfortunately, poor water management and corruption add to this list.

So far, there have been several responses to the food crisis. The first is the provision of aid to vulnerable groups. Since 2012, the World Food Programme has assisted Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Actually, 90% of Syrian refugees in Lebanon now find themselves living in conditions of extreme poverty. Since the crisis began in October 2019, food costs have increased 19 times. The Wheat Supply Emergency Response Project was the second response to this food crisis. Lebanon received a USD150 million loan from the World Bank, effectively sustaining wheat subsidies despite a rise in the exchange rate from USD/LBP 15,000 to 30,000 in October 2023. In May 2023, more availability and access to USD, more job possibilities, and a continuous supply of subsidised wheat helped ease access to food and other vital resources.

Additionally, the World Food Programme's Country Strategic Plan for 2023-2025 is a strategic contingency mechanism against financial system shocks. Since the situation has escalated along the Blue Line in the South of Lebanon, 462 Hectares of agricultural land have been burnt, and 300k animals have been killed, aggravating the food insecurity in this area. Furthermore, OCHA’s Humanitarian Country Team has provided water, meals and food parcels, nutritional supplements, cash assistance and health services.

Conclusion

Lebanon is witnessing an unprecedented crisis, intertwining economic challenges, political instability, and social upheaval. This has led to a severe economic downturn marked by currency depreciation, hyperinflation, and growing unemployment. Vulnerable populations bear a disproportionate burden, while political instability undermines effective governance and exacerbates economic issues. Lebanon's weakened international standing and the recent violence pose additional threats to recovery. Despite initial hopes for 2024, the outlook could be better. Lebanon stands at a critical juncture, requiring collaborative efforts for a sustainable and prosperous future. The increasingly tumultuous political scene that started escalating last Autumn does not contribute to improving the country's economic and food security. Although there was a glimpse of hope last year prompted by the responses to the food crisis, food insecurity persists in Lebanon.

The country's food security status is weak and in danger of worsening over time. Continuous work is needed to combat food insecurity and protect vulnerable groups (e.g. refugees). Violence, political and economic uncertainty, inflation, and discontinuing food aid do not hamper this crisis. These factors indicate that food insecurity will likely worsen in the upcoming months.