Authors: Igor Shchebetun, Fabrizio Napoli, Davide Gobbicchi and Greta Bordin.

A war without logistics is simply an outrage.

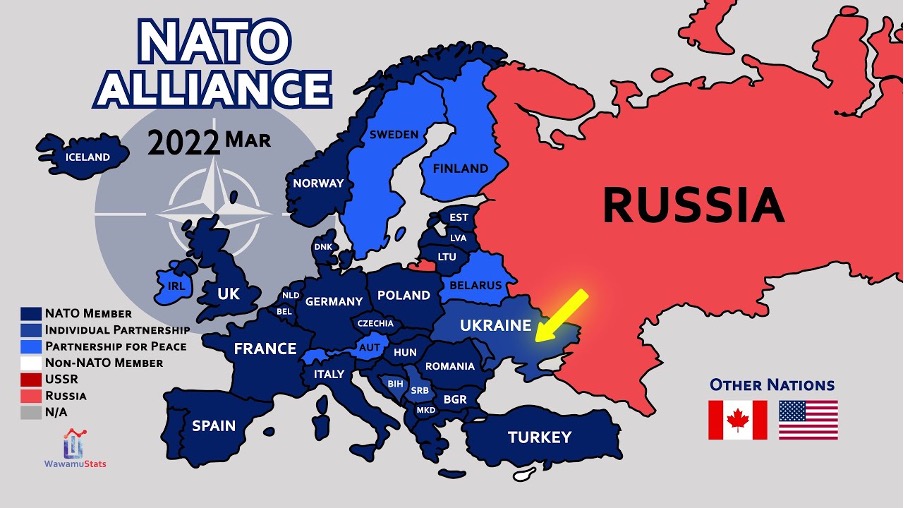

At the very beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian conflict, the kilometer-long queue of Russian armor entering Ukraine was simply stretched so far that it could not ensure maneuverability, safety and combat effectiveness in terms of deployment in combat formation and readiness to attack or repel attacks. Looking at the first few days, it is clear that the Russian forces have not made as much progress as they originally planned. The reason for this is that the Russian armed forces are primarily an artillery army, but so far they have used some of their available firepower. Russia is essentially trying to carry out a full-scale invasion without the military operations it would require. And as shocking as the scenes from some cities may seem, Russia is looking for a cheap and easy victory with low civilian casualties. In other words, Russia is holding back as they represent themselves. However, as sanctions steadily take effect, Putin escalate the lethality of his war plan. Achieving a breakthrough without getting in the mud. For Ukrainians, this means the worst is yet to come. Like jumping into a pool before checking for water, Russia's invasion of Ukraine is not going according to plan. Technically, Ukraine and Russia have been at war since 2014. The violence has never stopped, but the recent attack is something else.

A new chapter in Ukraine's struggle for statehood. Russia's original plan included a "mad dash" into Kiev, forcing the Ukrainian government to capitulate, while pushing small units to quickly seize strategic transport interchanges to avoid a larger clash with Ukrainian forces. This is a strategy similar to the 2014 seizure of Crimea, when Russian green men forced Ukrainian troops out of their bases but they could not and showed Russia real face in action . Then, as now, the plan of attack was to win with little cost and few civilian casualties. The Russian leadership entered this war knowing that it would be extremely unpopular at home. So they sought to keep death and destruction to a minimum. As a result, the Russian military attempted comes to mass casualties, abuse of civilians, mass rape, destruction of the Ukrainian people and their identity through genocide. What Russia is doing in Ukraine can best be described Putin’s Russia ideology and they values.

Regardless huge experience of military operations Russian army has performed poorly. Ukrainian forces fought back hard, exceeding expectations and playing on Russia's logistical vulnerabilities. For example, by blowing up railroads from and to Russia, Ukraine forced Russian Logistics to switch from rail transport to truck transport. Ukrainian fighters on the ground and Bayraktar drones in the air then targeted these field trucks. Without fuel, tanks and other vehicles are useless. And fuel trucks are an easier target than tanks. Thus, Ukraine played on Russia's self-confidence. At the same time, Russian units are not fighting an all-out war. Instead, in the first few days we saw small units advancing, tanks moving without infantry, planes flying into hostile airspace, and supplies running low. Much of Russia's decision-making seems unnecessary and risky. Instead of operational needs, tactical planning is driven by institutional needs. Probably on the grounds Russians thought they could avoid heavy fighting, at least initially. Moreover, the Kremlin underestimated the Ukrainian will to fight. For example, after several days of fighting in Ukraine and after Russian troops began to suffer casualties, the Russian Ministry of Health mobilized civilian doctors throughout the country.

The fact that the Russians did not do so on the first day suggests that they did not expect things to go so badly. In fact, the Kremlin tried to win the victory at little cost and to do it quickly in order to avoid the worst of the sanctions. Now they find themselves in the worst of all worlds. Putting resources into a bad strategy. That said, Ukraine would not want to celebrate too soon. Although the Russian leadership has underestimated Ukraine's will for war, it would also be a mistake to measure the strength of the Russian army by its territorial gains. The Russian full invasion especially considering the impossibility of providing and supplying all or at least the bare necessities of their mobilized has nothing to boast about so far. But the leadership in Moscow does not have the resources for a prolonged violent occupation. Social and political pressure is already beginning to show inside Russia. The war in Ukraine is unpopular and unexpected, and as the death toll continues to rise, anti-war sentiment in Russia is likely to intensify by the day. Putin needs a resolution to the war, or he will create serious problems at home. However, he cannot back down now without losing face.

Thus, the Kremlin need to intensify the lethality of its military plan and they do that to achieve its goals and achieve some kind of breakthrough. The Russian military started striking public infrastructure and residential areas. Civilian casualties increased, and the goal would be to force Zelensky into negotiations. But as we can see, Russia has forgotten the lessons of Ukrainian history and has drowned in its own illusions that Ukrainians and Russians are one people. Different mentality, values, attitude to people, to hostages and to the enemy, the concept of development, the art of fighting and the will to win appear more and more.

Putin's plank for a negotiated solution is for Ukraine to cede Crimea to Russia and agree to some form of neutrality or federalization and perhaps a constitutional restriction on the Ukrainian army, something like the Japanese situation. Zelensky is unlikely to agree to these demands, which means that the fight will drag on for some time. And this is where predictions become unreliable. The longer the war goes on, the more the Ukrainian battle space becomes similar to the Syrian one, but the opposite is also true: the longer the fighting goes on, the more sanctions will be imposed. A prolonged war will damage Ukraine, but it will also shake the foundations of Putin's power at home. And while a palace coup remains unlikely, as the war reaches home, the odds of success will gradually turn against Putin. So now the Russian leadership is in rescue mode. They need to get out of Ukraine while saving face. It is in Putin's interest to start negotiations as early as possible, while Zelensky would be doing the right thing if he delayed negotiations until sanctions begin to cut into Russia's skin, albeit at the risk of ruining Ukraine.